This post is also available in:

Italiano (Italian)

Italiano (Italian)

The Wonder Clockmaker

By Paolo Somigli, Libera Università di Bolzano

Born on May 28, 1923, to a Hungarian family in what is present-day Târnăveni, a village in Transylvania that became part of Romania after the end of World War I, György Ligeti was one of the most important, representative, and original figures of 20th-century music. He navigated different compositional and aesthetic trends, always with his own distinct identity. This allowed him not only to realize these trends in a personal vision, often connected to forms of more or less evident reference to the tradition of music history, but also to observe them with detachment and sometimes subject them to severe criticism on both theoretical and compositional levels. This is exemplified by the selection of works chosen for the Focus 2024 of the Accademia Chigiana.

Ligeti’s foundations are rooted in a multitude of influences, connected to his educational journey and the events of his homeland. During his early years of musical training in the Transylvanian city of Cluj-Napoca (which was again Hungarian between 1940 and 1944), he particularly studied the composers of the great classical-romantic repertoire. After World War II, he moved to Budapest and enrolled in the “Franz Liszt” Academy. Among his teachers were Zoltán Kodály, a proponent of the rediscovery of Hungarian folk singing as a fundamental element of pedagogy, and Sándor Veress, who placed significant emphasis on the study of counterpoint and polyphony, starting from the great masters of Renaissance. During the same period, he delved deeply into both the figure and work of Béla Bartók, who died in 1945, as well as Transylvanian and Romanian musical traditions, with a period of study and research in Romania between 1949 and 1950.

His output from the period between the 1940s and the early 1950s is thus rich and multifaceted, encompassing the recovery of Hungarian (and also Romanian) folk heritage, historical references, and experimentation. This is evidenced by the works included in the program, such as pieces based on Hungarian folk music like Magos kösziklána (1946; not performed until 1994), Lakodalmas (Wedding Dance; 1950), and Gomb, gomb from Mátraszentimre Dalok (Songs from Mátraszentimre; 1955), the more daring Éjszaka and Reggel (Night and Morning; 1955) on texts by his poet friend Sándor Weöres, as well as instrumental works such as the Sonata for Cello (1948-1953), Musica ricercata (1951-1953), the Six Bagatelles (1953), and the String Quartet No. 1, ‘Métamorphosen nocturnes’ (1953-54).

A common thread links these instrumental works: the reception of stimuli from Bartók and Kodály, but also from the tradition of historical art music, the use of short pieces, and an organization into episodes arranged in terms of succession and juxtaposition. The Sonata for Cello, which already in its title highlights the intentional reference to tradition, consists of two short movements written at different times (1948: Dialogue; 1953: Capriccio) for two different performers. It complementarily shows us two facets of the composer, with the lyricism and folk melody of the Dialogue and the frenzied Bartókian aggressiveness of the Capriccio. Musica ricercata, which gained significant popularity in recent times due to the inclusion of its second piece in Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999), is also based on the short piece. The composition is divided into eleven episodes, with a progressive expansion of the pitches used in each. From the first piece, based on a single note, A, to which an unexpected D is added at the last moment, it gradually progresses to the use of the full chromatic scale in the final piece. Only at this point does Ligeti reveal the reason for the title: the reference to the “Chromatic Ricercar” from Frescobaldi’s Messa degli Angeli in Fiori musicali. From Musica ricercata, Ligeti derived the Six Bagatelles for Wind Instruments in 1953.

The String Quartet No. 1, ‘Métamorphoses nocturnes,’ although structured in a single movement, also proceeds through short episodes in which the influence of Bartók’s world is clearly perceptible, at the rhythmic level, melodic configurations, and sound atmospheres; however, it coexists with reminiscences of Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite, a score Ligeti had been able to examine in the Academy’s library. Not only a common constructive thread but also a shared fate links these works: none of them (with the partial exception of the Bagatelles) were performed at the time of their composition or overcame the resistance of censorship due to their alleged excessive modernity.

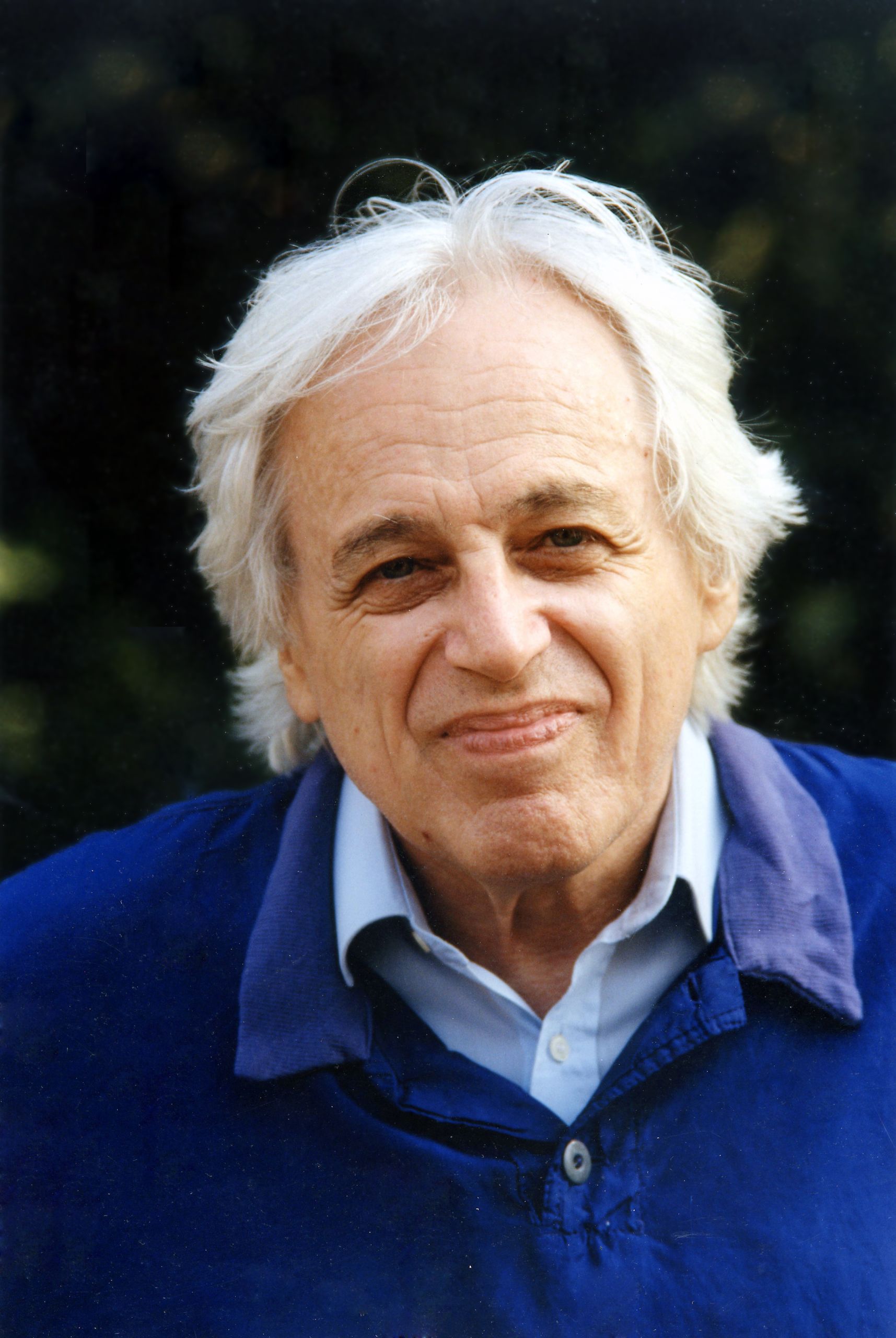

György Ligeti, Artikulation, Electronic Music, An Aural Score by Rainer Wehinger – Schott Music 6378-20, © 1970 B. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz [2° system, p. 50]

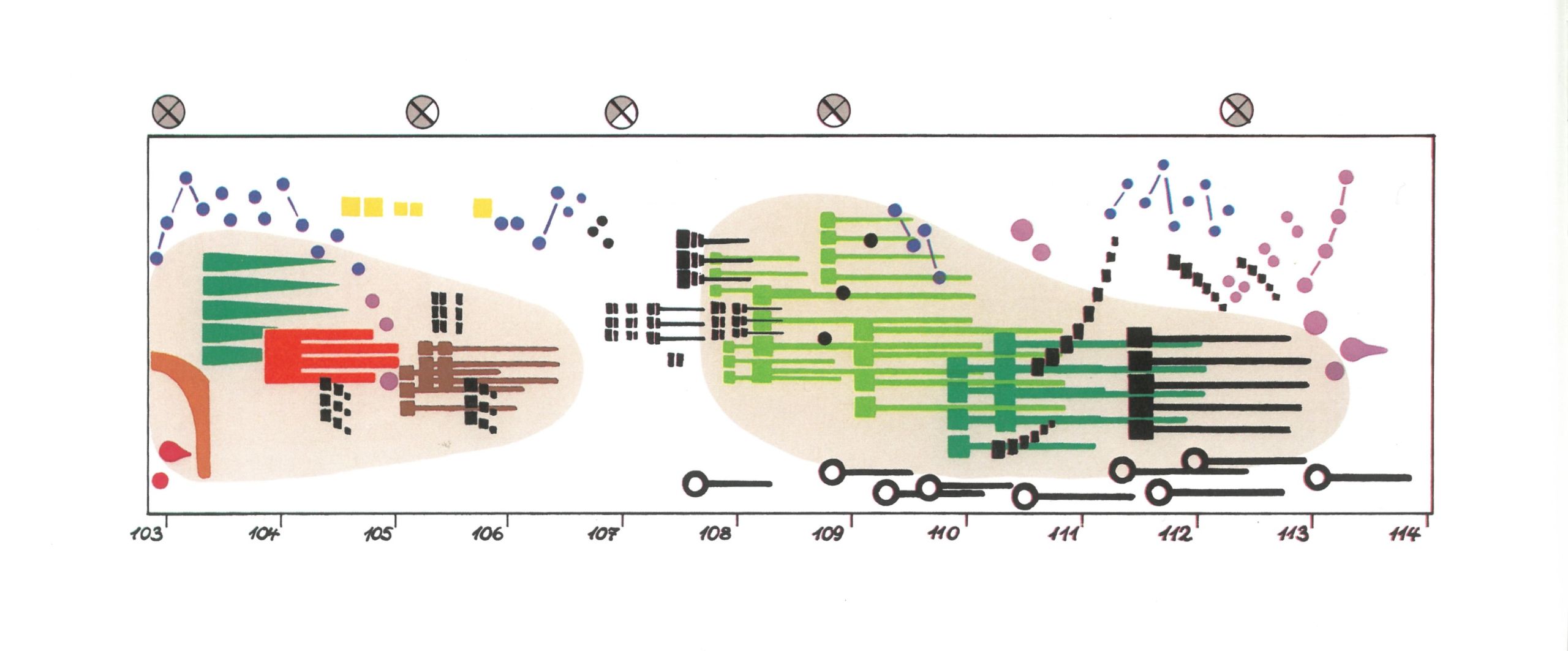

György Ligeti, Artikulation, Electronic Music, An Aural Score by Rainer Wehinger – Schott Music 6378-20, © 1970 B. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz [1° system, p. 52]

The political and cultural climate of 1950s Hungary was marked by a phase of extreme closure and subjection to the dictates from the Soviet Union until about the mid-decade, followed by a period of greater independence that culminated in the Budapest uprising of October 1956. Particularly between 1955 and 1956, there was a new openness to 20th-century currents in the artistic field: Ligeti himself was able to delve into the music and compositional method of Arnold Schönberg and approach contemporary avant-garde movements. The Soviet intervention on November 4, 1956, ended that brief period. However, in December, Ligeti managed to escape from the country.

The escape from Hungary led to a radical artistic transformation. This transformation grafted onto traits and characteristics of the previous period in a tension that we might define as dialectical; it manifested, among other things, in a form of temporary distancing from anything that could openly show a connection with what had characterized his years of training and work in Hungary.

Finally in direct contact with the music and composers he had previously only heard on radio broadcasts, often clandestinely, Ligeti soon became a leading figure in the wave of renewal and its associated debates. These found their main engines in the Electronic Music Studio of WDR in Cologne, where Ligeti developed a close relationship with Karlheinz Stockhausen, and at the Internationale Ferienkurse für neue Musik in Darmstadt, where he attended as a student in 1957 and returned as a lecturer by 1959. He immediately contributed to electroacoustic experimentation with two seminal works, Glissandi (1957) and Artikulation (1958), complemented by Pièce électronique n.3 (1957-58), which remained on paper until the 1990s when it was realized sonically thanks to Kees Tazelaar and Johan van Kreij of the Institute of Sonology in The Hague.

In the debate on compositional trends, particularly on the inevitable contradictions of fully predetermined composition pursued until the mid-1950s within the Darmstadt context, Ligeti made a formidable contribution with the publication in 1958 of a rigorous and incisive analysis of Pierre Boulez’s Structures Ia.

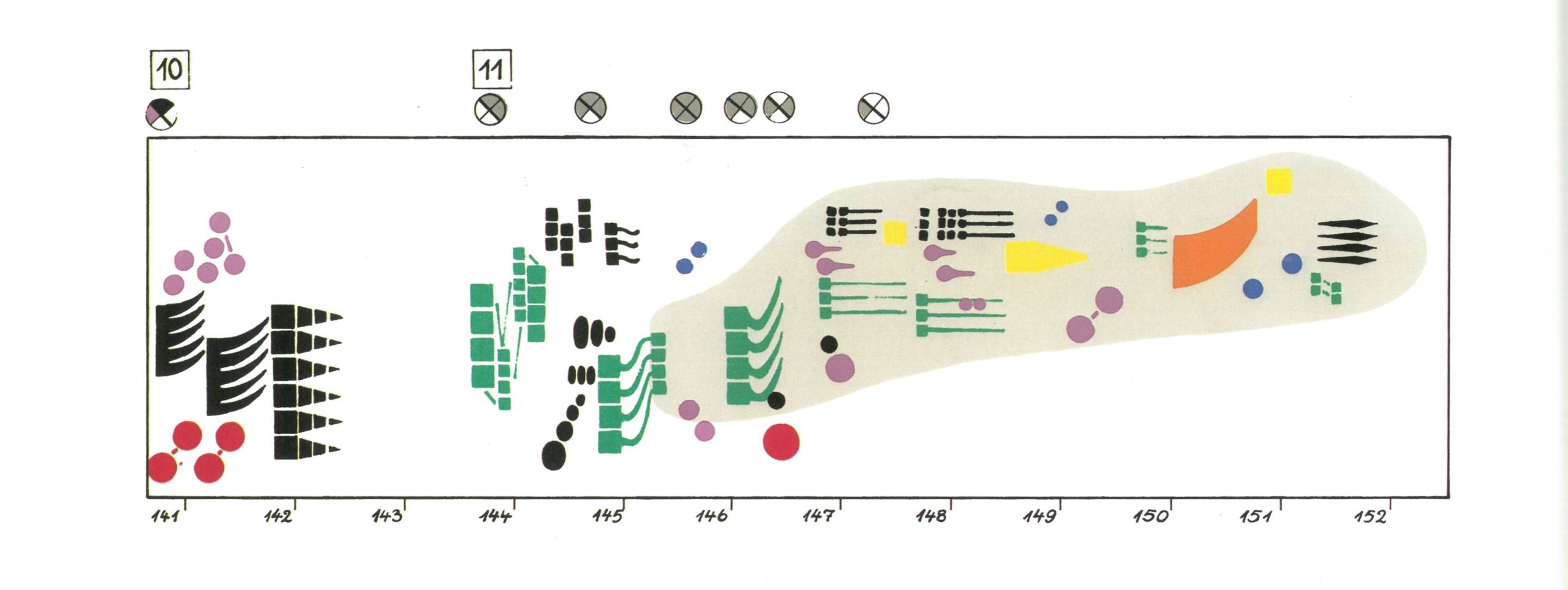

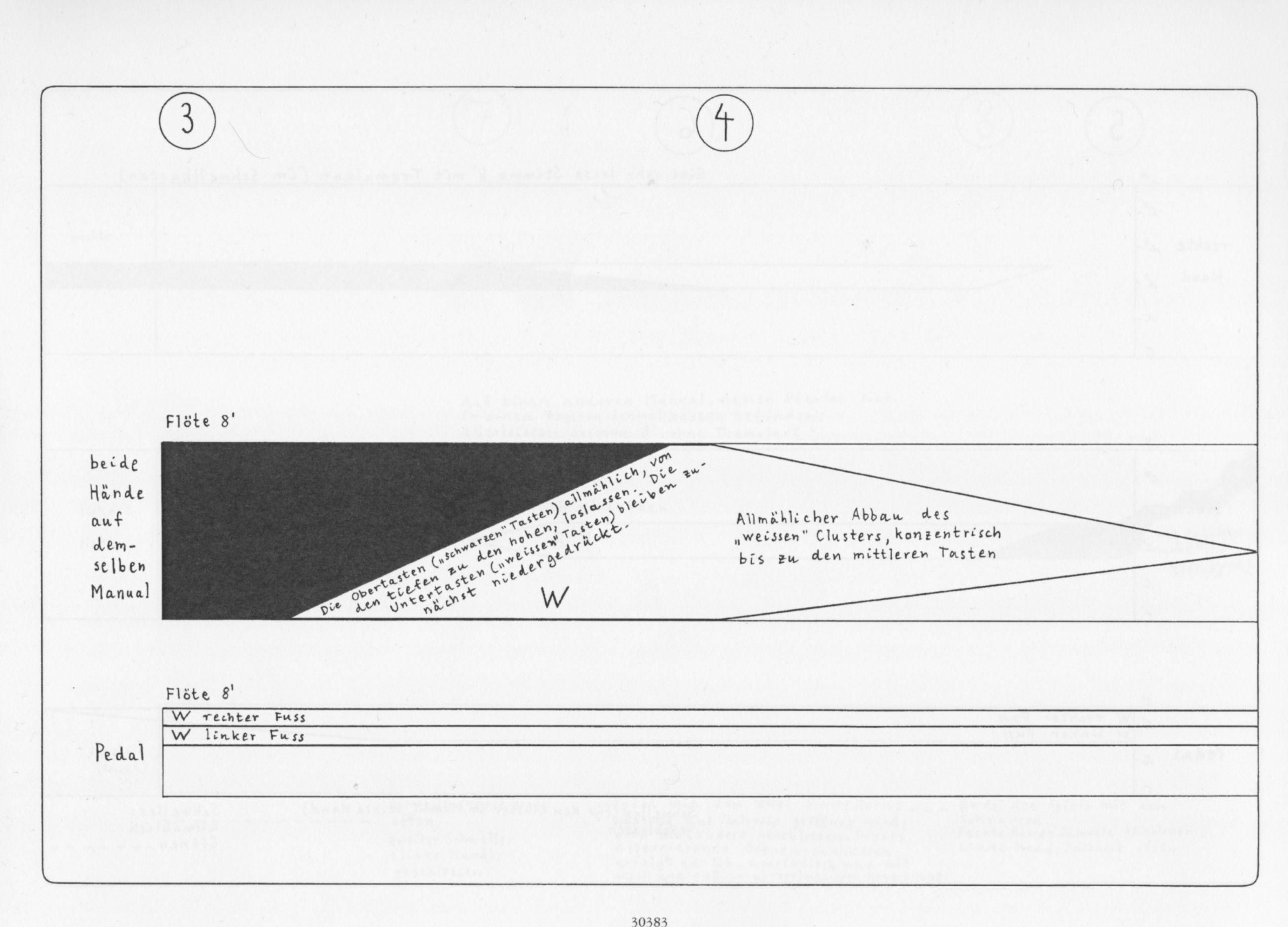

György Ligeti, Volumina, for organ (1961-62/rev. 1966) – Edition Peters 5983, n. 30383, © 1967 by Henry Litolff’s Verlag Ltd & Co. KG, Leipzig [pp. 1-2]

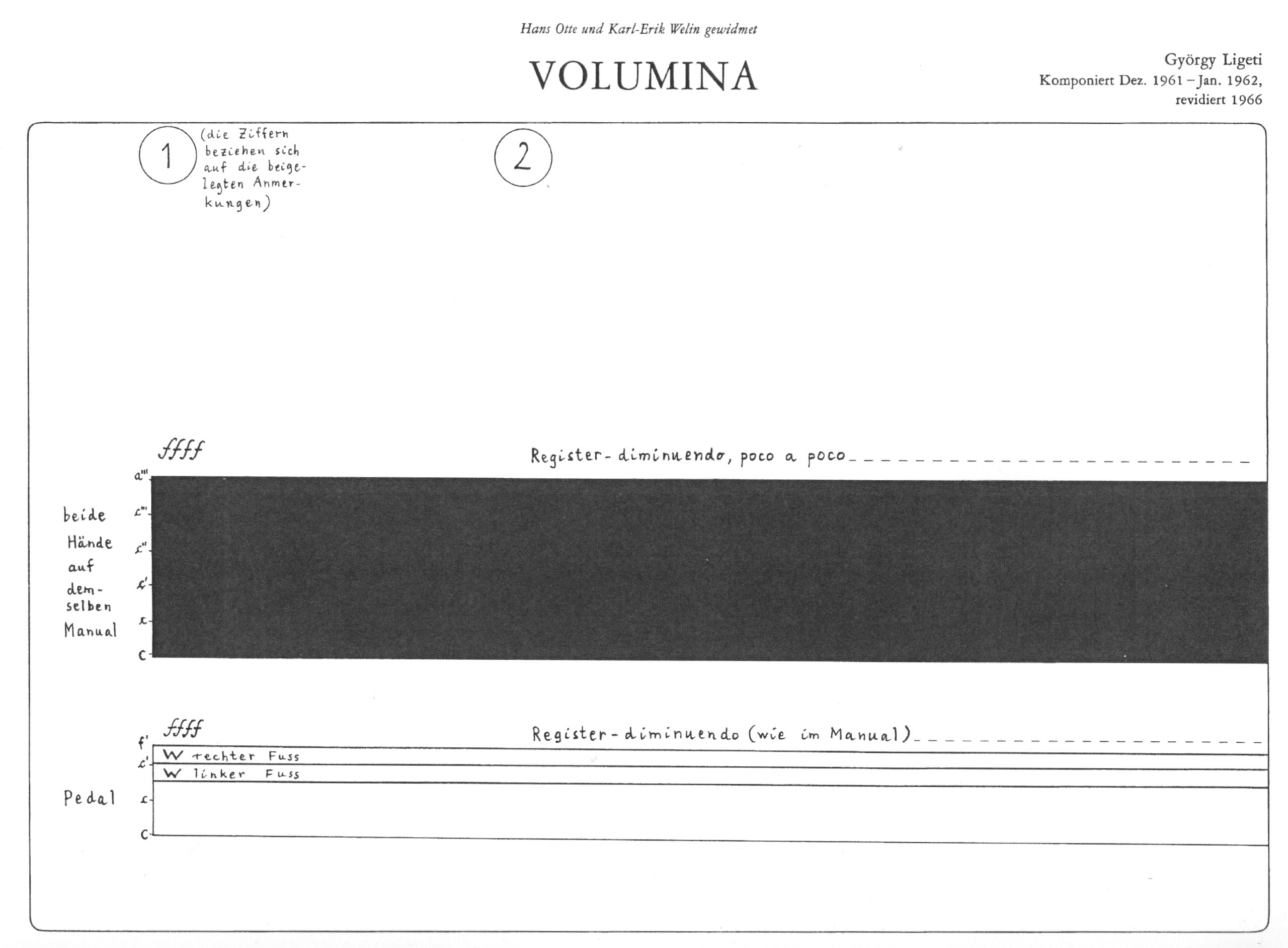

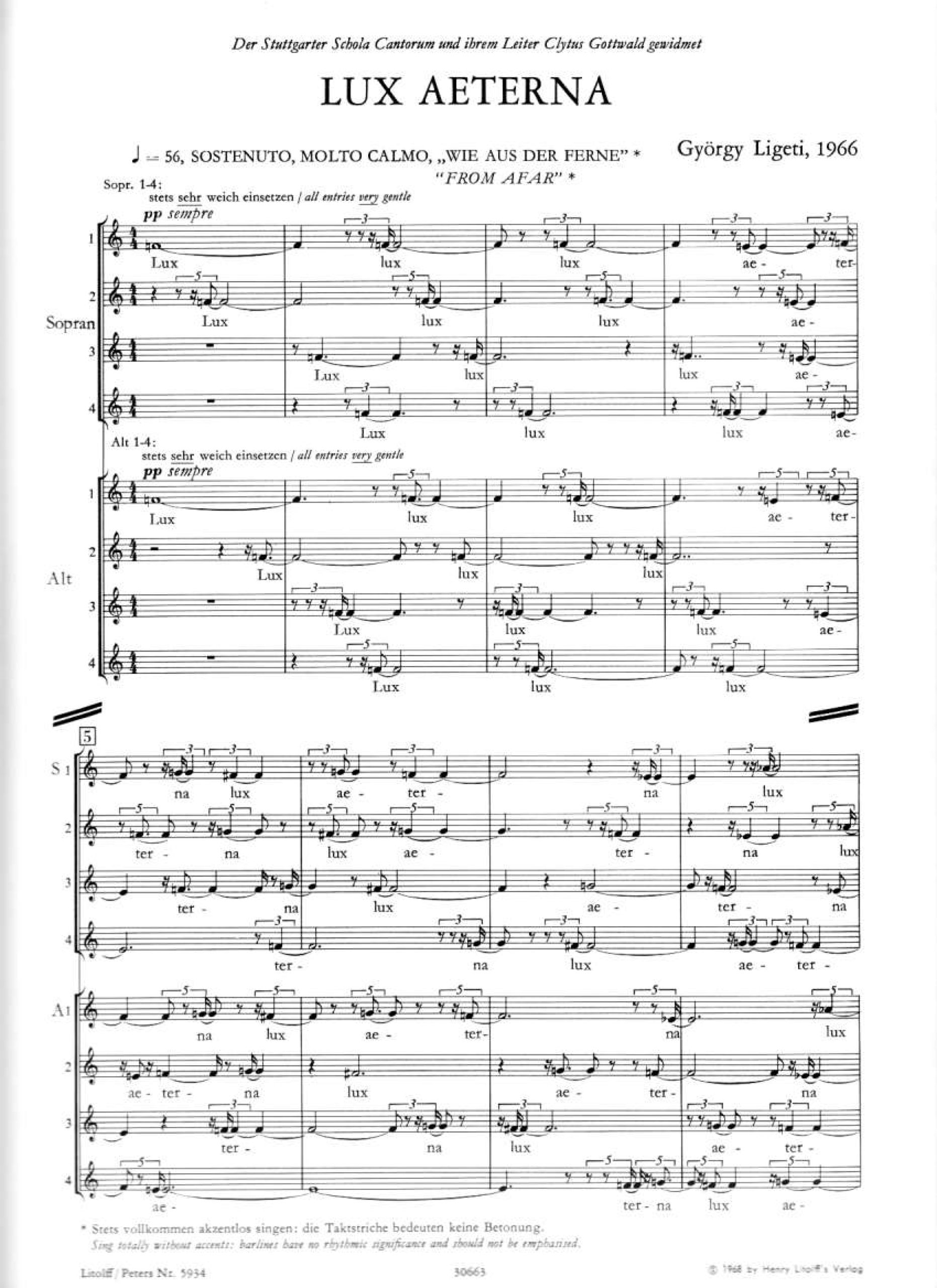

György Ligeti, Lux Aeterna (1966)- Peters Edition 5934, n. 30663, © 1968 by Henry Litolff’s Verlag [p. 1]

In the same period, in line with the developments of the debate in that context, his approach to semi-aleatoric forms of composition and the search for new types of notation became evident. These new notations went beyond the mere indication of sound parameters to suggest ranges of pitches, timbres, and actions to be performed by the musician. An extraordinary example of Ligeti’s personal approach is Volumina for organ: on one hand, its score can be considered emblematic of the aforementioned trend, and on the other hand, Ligeti highlights its reference to the ideal model of the Bachian passacaglia. This work, written between 1961 and 1962, was revised by Ligeti in 1966, on the eve of composing Harmonies (1967), which is based on a slow succession of linked sound aggregates and is the first of his Two Studies for Organ (1969).

The reference to Johann Sebastian Bach in regard to Volumina is part of a broader context in which, during the same period, Ligeti dedicated himself to further deepening polyphonic writing—studied, as previously noted, since his formative years—until he developed a completely original implementation, destined to define his art. Contrapuntal elaboration characterizes many works from the 1960s, including the crucial Atmosphères (1961), where the composer offered one of the first, complete examples of his “micropolyphony.” In this work, each of the 48 polyphonic parts contributes to creating an overall acoustic effect where the perception of individual part entries is lost, giving way to a controlled and kaleidoscopic cluster, a sound aggregate in slow and continuous transformation.

This writing style also marks his vocal production of the decade, where Ligeti revisited the tradition of sacred music through works like Requiem (1963-65) and Lux Aeterna (1966), both also known to the general public for their presence in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Lux Aeterna can be considered a sort of offshoot of the earlier work. Ligeti wrote it in 1966, after completing the Requiem with the “Lacrimosa.” Micropolyphony here is realized in its quintessence, with writing for sixteen a cappella parts and an effect of slow, almost static yet progressively shifting sound, making the entrances and exits of voices imperceptible or, conversely, sharply outlined.

The reflection on polyphonic writing and the adoption of micropolyphony in connection with the investigation of the modalities of sound and musical perception led to another typical aspect of Ligeti’s poetics and music: the phenomenon of “illusory” rhythms and melodies. The superimposition of differentiated rhythmic modules, as well as the prominence of certain repeated pitches within a continuous design, creates in the listener’s mind the emergence of additional rhythmic-melodic figures, temporalities, and overlaps beyond what is present on the page. This effect is achieved with overlapping rhythmic or rhythmic-melodic modules characterized by progressive shifts. From this calculated and rigorous writing, which Ligeti also refers to by analogy with the mechanism of a clock, a rhythmic-melodic kaleidoscope is born. Played upon the listener’s perception, it ensnares the listener in its ever-changing yet inexorable grids.

Extraordinary examples of this aspect can be found in the Kammerkonzert for 13 instrumentalists (winds, strings, piano, and harpsichord; 1969-70), a piece in four movements, the third of which is marked “Movimento preciso e meccanico” (“Precise and mechanical movement”), as well as in a solo work like Continuum for harpsichord (1968). In Continuum, the execution speed of an uninterrupted sequence of sixteenth notes not only generates inexhaustible and ever-changing rhythmic and melodic figures with additional illusory effects of acceleration and deceleration but also “liquefies” the plucked and metallic sound of the instrument into a unified flow; it almost transfigures it into electronic sonorities.

Micropolyphonic writing, with its related consequences, is also found in the String Quartet No. 2 (composed in 1968 and premiered in Baden-Baden in 1969), in which the five movements converge various characteristic features of the composer’s work into a milestone of 20th-century quartet music, and in the orchestral Ramifications (1968-69). In Ramifications, Ligeti further develops his research on sound by prescribing that half of the instruments play “in scordatura,” tuned a quarter tone higher than usual. This feature will reappear, realized in more complex terms, in the Violin Concerto.

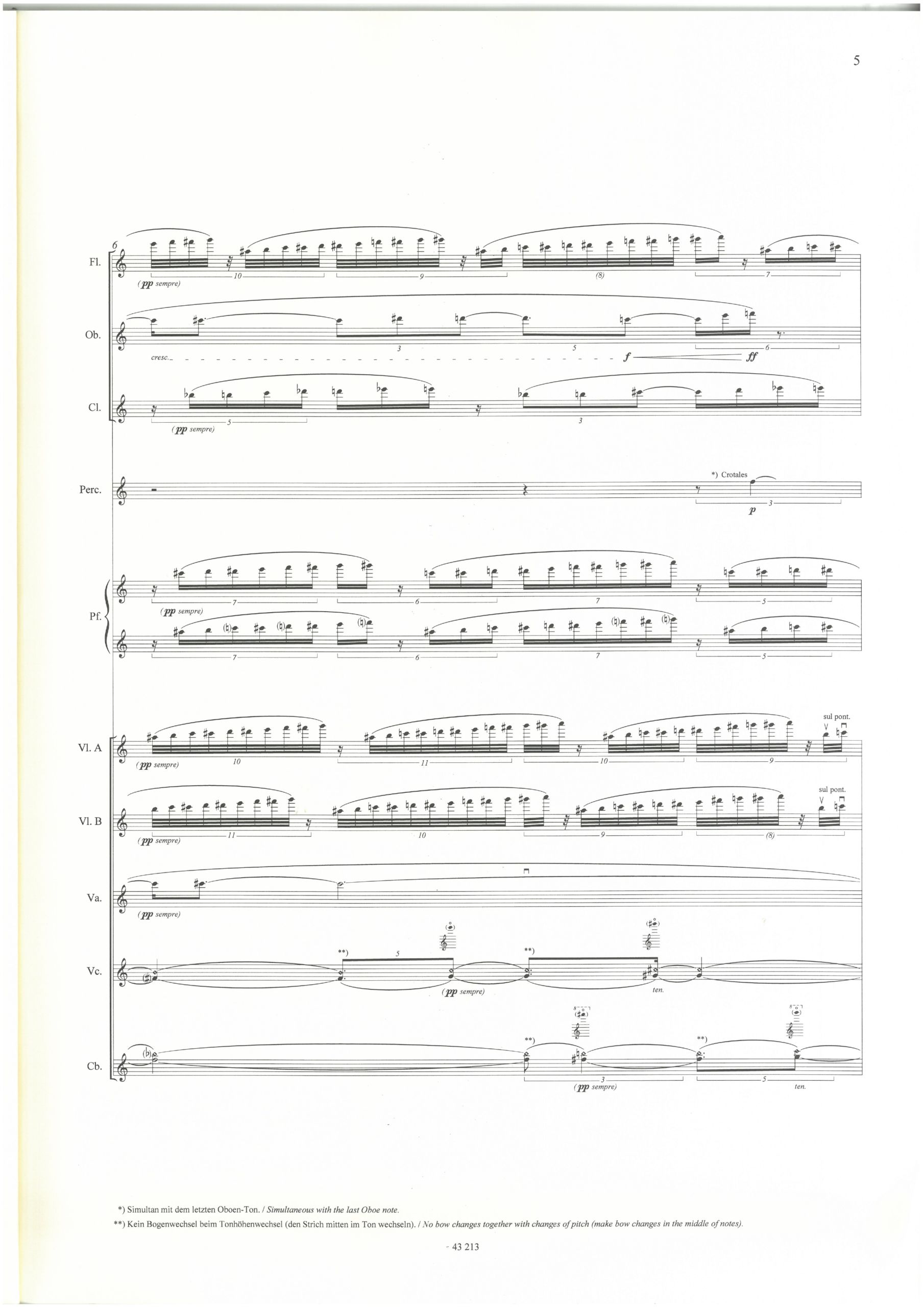

György Ligeti, Melodien (1971) – Schott Music 43 213, © 2013 Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, Mainz [partitura, p. 5]

The elaboration of the constructive aspects just mentioned finds an additional point of synthesis and at the same time development in Melodien for orchestra (1971), in which Ligeti envisions – as he writes in the score – “a variety of divergent tempos and rhythmic articulations” and the stratification of sound events on as many as “three dynamic planes: a ‘foreground’ consisting of melodies and short melodic figures, a middle ground consisting of subordinate figurations, and a ‘background’ made up of long sustained sounds.”

Ligeti would return to the harpsichord and its metallic timbre at the end of the 1970s with two works related to his teaching activity in composition in Hamburg: Hungarian Passacaglia and Hungarian Rock, both from 1978. These pieces are characterized by a sort of mutual opposition: the first consists of a process of progressive acceleration on an ostinato motif according to the form of a passacaglia; the second is a fast and frenetic piece in the form of a chaconne reimagined in a rock style that transitions to a slow and rarefied conclusion.

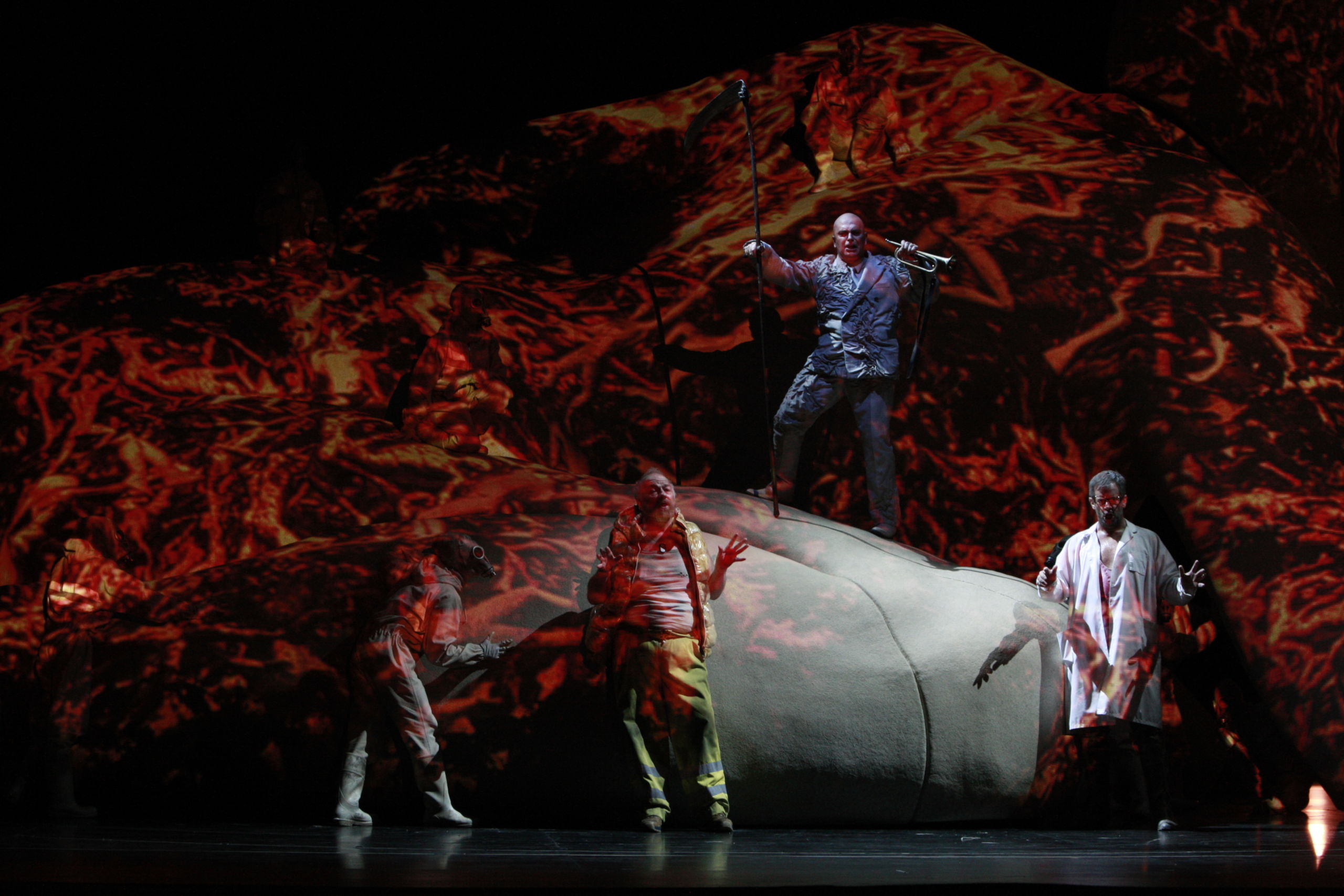

The new explicit reference to these historical forms in a context of evident experimentation once again shows how deeply rooted Ligeti’s intent is to maintain an evident continuity with tradition. At the same time, it illustrates how this tradition continues to be reinterpreted in an open, critical, and dialectical vision, which is not without a form of conscious and ironic detachment. It is within this perspective that the unique work Le grand macabre (1974-77) is situated. This is Ligeti’s only theatrical opera, conceived as a sort of desecrating pastiche under the shadow of a grotesque end of the world. With fantastic and profound irony, he brings together practically the entire history of opera.

The reference to tradition, updated to the point of eclecticism and in an increasingly openly post-modern perspective, characterizes Ligeti’s composition from the 1980s onwards.

In the middle of the decade, Ligeti completed the first of his three books of Études for piano (1985: I, 1988-94: II, 1995-2001: III). Thus began a cycle of 18 highly virtuosic and visionary piano pieces, in which the historical perspective encompassing Chopin, Liszt, Scriabin, and Debussy, as highlighted by the title, is combined not only with the rhythmic discoveries and experiments previously mentioned but also with deep influences from the player piano works of Conlon Nancarrow, the ethnomusicological research of Simha Arom, and the recordings of the Banda Linda people of Central Africa, as well as the Javanese gamelan (Galamb Borong) and Constantin Brâncuși’s sculpture (Endless Column).

Photo of the scene from Le grand macabre (1974-77/ rev. 1996) Music: György Ligeti, Libretto: György Ligeti, Michael Meschke, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, Stagione 2009, Conducting, Zoltan Peskò; Director, Alex Ollé, Valentina Carrasco; Scene, Alfons Flores; Costumi, Lluc Castells. [In order, from right: Nicholas Isherwood, Astradamors; Roberto Abbondanza, Nekrotzar; Chris Merritt, Piet “La Botte”] credits: Falsini, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma.

This is also the period of Ligeti’s Piano Concertos (1985-88) and Violin Concerto (1990-92), through which he offered his reinterpretation of these historical forms and genres. The general meaning of the term “concerto” can be inferred both from the notes the composer wrote as early as 1966 for the Cello Concerto and from some of his statements in the 1990s.

From Ligeti’s perspective, the fundamental nucleus of the “concerto” lies primarily in the interaction, played with extreme virtuosity, between a soloist and other instruments or the entire orchestra. Nevertheless, in Ligeti’s concertos, other characteristic aspects of the genre in terms of organizational and formal structure come into play, along with additional elements related to the composer’s relationship with both the history of music and his contemporary era.

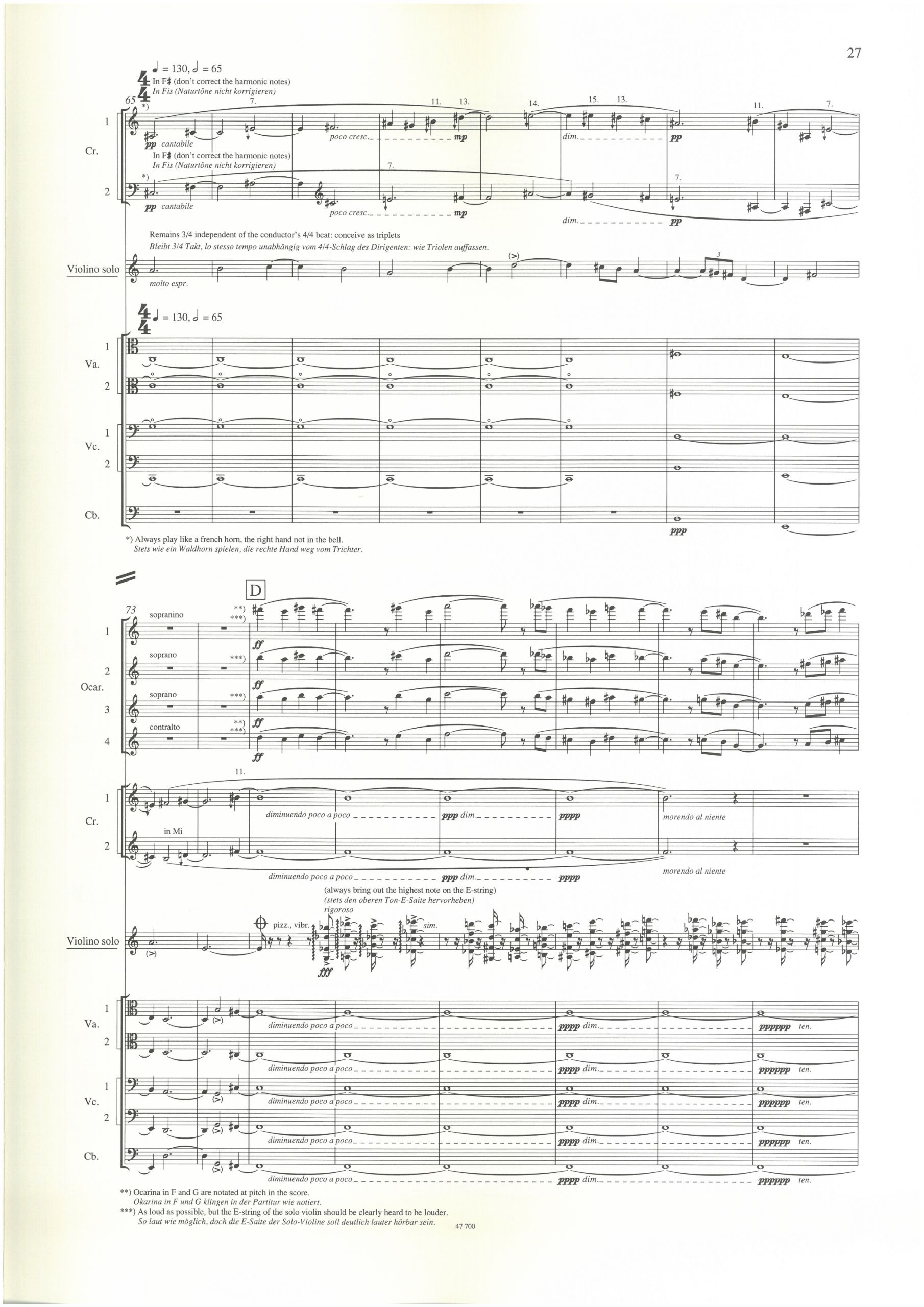

György Ligeti, Konzert für Violine und Orchester – Schott Music 47 700 – © 1992 Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, Mainz 47 700 [score, p. 27]